# Preparing a Raspberry Pi

This guide will walk you through how run a Rocket Pool node using a Raspberry Pi. While this is not typically recommended in most staking guides, we recognize that it is attractive because it is a much more affordable option than standing up an entire PC. To that end, we've worked hard to tweak and optimize a whole host of settings and have determined a configuration that seems to work well.

This setup will run a full Execution (ETH1) node and a full Consensus (ETH2) node on the Pi, making your system contribute to the health of the Etherum network while simultaneously acting as a Rocket Pool node operator.

NOTE

This setup works well with the current implementations of Execution (ETH1) and Consensus (ETH2). It's possible that after the merge of the Execution (ETH1) chain and the beacon chain, a full node may be more computationally demanding. While we have been advised that this is unlikely, there is a chance that the Raspberry Pi may not be able to run a full node post-merge. Please factor this into your decision before settling on it as a node platform.

# Preliminary Setup

To run a Rocket Pool node on a Raspberry Pi, you'll need to first have a working Raspberry Pi. If you already have one up and running - great! You can skip down to the Mounting the SSD section. Just make sure you have a fan attached before you go. If you're starting from scratch, then read on.

# What You'll Need

These are the recommended components that you'll need to buy in order to run Rocket Pool on a Pi:

- A Raspberry Pi 4 Model B, the 8 GB model

- Note: while you can use a 4 GB with this setup, we strongly recommend you go with an 8 GB for peace of mind... it's really not much more expensive.

- A USB-C power supply for the Pi. You want one that provides at least 3 amps.

- A MicroSD card. It doesn't have to be big, 16 GB is plenty and they're pretty cheap now... but it should be at least a Class 10 (U1).

- A MicroSD to USB adapter for your PC. This is needed so you can install the Operating System onto the card before loading it into the Pi. If your PC already has an SD port, then you don't need to pick up a new one.

- Some heatsinks. You're going to be running the Pi under heavy load 24/7, and it's going to get hot. Heatsinks will help so it doesn't throttle itself. You ideally want a set of 3: one for the CPU, one for the RAM, and one for the USB controller. Here is a good example of a nice set (opens new window).

- A case. There are two ways to go here: with a fan, and fanless.

- With a fan:

- A 40mm fan. Same as the above, the goal is to keep things cool while running your Rocket Pool node.

- A case with a fan mount to tie it all together. You could also get a case with integrated fans like this one (opens new window) so you don't have to buy the fans separately.

- Without a fan:

- A fanless case that acts as one giant heatsink, like this one (opens new window). This is a nice option since it's silent, but your Pi will get quite hot - especially during the initial blockchain sync process. Credit to Discord user Ken for pointing us in this direction!

- As a general rule, we recommend going with a fan because we're going to be overclocking the Pi significantly.

- With a fan:

You can get a lot of this stuff bundled together for convenience - for example, Canakit offers a kit (opens new window) with many components included. However, you might be able to get it all cheaper if you get the parts separately (and if you have the equipment, you can 3D print your own Pi case (opens new window).)

Other components you'll need:

- A USB 3.0+ Solid State Drive. The general recommendation is for a 2 TB drive, but if it isn't in your budget, a 1 TB drive is acceptable for now.

- The Samsung T5 (opens new window) is an excellent example of one that is known to work well.

- ⚠️ Using a SATA SSD with a SATA-to-USB adapter is not recommended because of problems like this (opens new window). If you go this route, we've included a performance test you can use to check if it will work or not in the Testing the SSD's Performance section.

- An ethernet cable for internet access. It should be at least Cat 5e rated.

- Running a node over Wi-Fi is not recommended, but if you have no other option, you can do it instead of using an ethernet cable.

- A UPS to act as a power source if you ever lose electricity. The Pi really doesn't draw much power, so even a small UPS will last for a while, but generally the bigger, the better. Go with as big of a UPS as you can afford. Also, we recommend you attach your modem, router, and other network equipment to it as well - not much point keeping your Pi alive if your router dies.

Depending on your location, sales, your choice of SSD and UPS, and how many of these things you already have, you're probably going to end up spending around $200 to $500 USD for a complete setup.

# Making the Fan Run More Quietly

When you get the fan, by default you're probably going to be instructed to connect it to the 5v GPIO pin, as shown in the picture below.

The fan will have a connector with two holes; the black one should go to GND (pin 6), and the red one should go to +5v (pin 4).

However, in our experience, this makes the fan run very loud and fast which isn't really necessary. If you want to make it more quiet while still running cool, try connecting it to the 3.3v pin (Pin 1, the blue one) instead of the 5v pin. This means that on your fan, the black point will go to GND (pin 6) still, but now the red point will go to +3.3v (pin 1).

If your fan has a connector where the two holes are side by side and you can't split them apart, you can put some jumpers like this (opens new window) in between it and the GPIO pins on the Pi.

# Installing the Operating System

There are a few varieties of Linux OS that support the Raspberry Pi. For this guide, we're going to stick to Ubuntu 20.04. Ubuntu is a tried-and-true OS that's used around the world, and 20.04 is (at the time of this writing) the latest of the Long Term Support (LTS) versions, which means it will keep getting security patches for a very long time. If you'd rather stick with a different flavor of Linux like Raspbian, feel free to follow the existing installation guides for that - just keep in mind that this guide is built for Ubuntu, so not all of the instructions may match your OS.

The fine folks at Canonical have written up a wonderful guide on how to install the Ubuntu Server image onto a Pi (opens new window).

Follow steps 1 through 4 of the guide above for the Server setup.

For the Operating System image, you want to select Ubuntu Server 20.04.2 LTS (RPi 3/4/400) 64-bit server OS with long-term support for arm64 architectures.

If you decide that you want a desktop UI (so you can use a mouse and have windows to drag around), you'll need to follow step 5 as well. We suggest that you don't do this and just stick with the server image, because the desktop UI will add some additional overhead and processing work onto your Pi with relatively little benefit. However, if you're determined to run a desktop, then we recommend choosing the Xubuntu option. It's pretty lightweight on resources and very user friendly.

Once that's complete, you're ready to start preparing Ubuntu to run a Rocket Pool node. You can use the local terminal on it, or you can SSH in from your desktop / laptop as the installation guide suggests. The process will be the same either way, so do whatever's most convenient for you.

If you aren't familiar with ssh, take a look at the Intro to Secure Shell guide.

NOTE

At this point, you should strongly consider configuring your router to make your Pi's IP address static. This means that your Pi will have the same IP address forever, so you can always SSH into it using that IP address. Otherwise, it's possible that your Pi's IP could change at some point, and the above SSH command will no longer work. You'll have to enter your router's configuration to find out what your Pi's new IP address is.

Each router is different, so you will need to consult your router's documentation to learn how to assign a static IP address.

# Mounting the SSD

As you may have gathered, after following the above installation instructions, the core OS will be running off of the microSD card. That's not nearly large enough or fast enough to hold all of the Execution (ETH1) and Consensus (ETH2) blockchain data, which is where the SSD comes in. To use it, we have to set it up with a file system and mount it to the Pi.

# Connecting the SSD to the USB 3.0 Ports

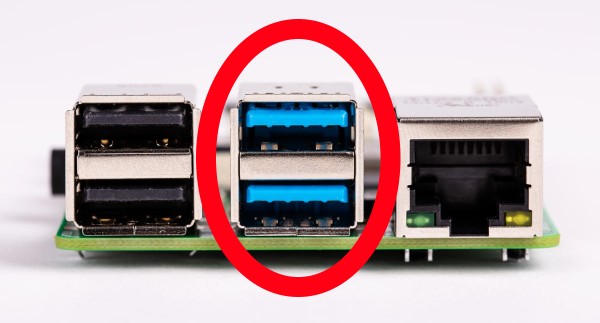

Start by plugging your SSD into one of the Pi's USB 3.0 ports. These are the blue ports, not the black ones:

The black ones are slow USB 2.0 ports; they're only good for accessories like mice and keyboards. If you have your keyboard plugged into the blue ports, take it out and plug it into the black ones now.

# Formatting the SSD and Creating a New Partition

WARNING

This process is going to erase everything on your SSD. If you already have a partition with stuff on it, SKIP THIS STEP because you're about to delete it all! If you've never used this SSD before and it's totally empty, then follow this step.

Run this command to find the location of your disk in the device table:

sudo lshw -C disk

*-disk

description: SCSI Disk

product: Portable SSD T5

vendor: Samsung

physical id: 0.0.0

bus info: scsi@0:0.0.0

logical name: /dev/sda

...

The important thing you need is the logical name: /dev/sda portion, or rather, the /dev/sda part of it.

We're going to call this the device location of your SSD.

For this guide, we'll just use /dev/sda as the device location - yours will probably be the same, but substitute it with whatever that command shows for the rest of the instructions.

Now that we know the device location, let's format it and make a new partition on it so we can actually use it. Again, these commands will delete whatever's already on the disk!

Create a new partition table:

sudo parted -s /dev/sda mklabel gpt unit GB mkpart primary ext4 0 100%

Format the new partition with the ext4 file system:

sudo mkfs -t ext4 /dev/sda1

Add a label to it (you don't have to do this, but it's fun):

sudo e2label /dev/sda1 "Rocket Drive"

Confirm that this worked by running the command below, which should show output like what you see here:

sudo blkid

...

/dev/sda1: LABEL="Rocket Drive" UUID="1ade40fd-1ea4-4c6e-99ea-ebb804d86266" TYPE="ext4" PARTLABEL="primary" PARTUUID="288bf76b-792c-4e6a-a049-cb6a4d23abc0"

If you see all of that, then you're good. Grab the UUID="..." output and put it somewhere temporarily, because you're going to need it in a minute.

# Optimizing the New Partition

Next, let's tune the new filesystem a little to optimize it for validator activity.

By default, ext4 will reserve 5% of its space for system processes. Since we don't need that on the SSD because it just stores the Execution (ETH1) and Consensus (ETH2) chain data, we can disable it:

sudo tune2fs -m 0 /dev/sda1

# Mounting and Enabling Automount

In order to use the drive, you have to mount it to the file system.

Create a new mount point anywhere you like (we'll use /mnt/rpdata here as an example, feel free to use that):

sudo mkdir /mnt/rpdata

Now, mount the new SSD partition to that folder:

sudo mount /dev/sda1 /mnt/rpdata

After this, the folder /mnt/rpdata will point to the SSD, so anything you write to that folder will live on the SSD.

This is where we're going to store the chain data for Execution (ETH1) and Consensus (ETH2).

Now, let's add it to the mounting table so it automatically mounts on startup.

Remember the UUID from the blkid command you used earlier?

This is where it will come in handy.

sudo nano /etc/fstab

This will open up an interactive file editor, which will look like this to start:

LABEL=writable / ext4 defaults 0 0

LABEL=system-boot /boot/firmware vfat defaults 0 1

Use the arrow keys to go down to the bottom line, and add this line to the end:

LABEL=writable / ext4 defaults 0 0

LABEL=system-boot /boot/firmware vfat defaults 0 1

UUID=1ade40fd-1ea4-4c6e-99ea-ebb804d86266 /mnt/rpdata ext4 defaults 0 0

Replace the value in UUID=... with the one from your disk, then press Ctrl+O and Enter to save, then Ctrl+X and Enter to exit.

Now the SSD will be automatically mounted when you reboot. Nice!

# Testing the SSD's Performance

Before going any further, you should test your SSD's read/write speed and how many I/O requests it can handle per second (IOPS). If your SSD is too slow, then it won't work well for a Rocket Pool node and you're going to end up losing money over time.

To test it, we're going to use a program called fio. Install it like this:

sudo apt install fio

Next, move to your SSD's mount point:

cd /mnt/rpdata

Now, run this command to test the SSD performance:

sudo fio --randrepeat=1 --ioengine=libaio --direct=1 --gtod_reduce=1 --name=test --filename=test --bs=4k --iodepth=64 --size=4G --readwrite=randrw --rwmixread=75

The output should look like this:

test: (g=0): rw=randrw, bs=(R) 4096B-4096B, (W) 4096B-4096B, (T) 4096B-4096B, ioengine=libaio, iodepth=64

fio-3.16

Starting 1 process

test: Laying out IO file (1 file / 4096MiB)

Jobs: 1 (f=1): [m(1)][100.0%][r=63.9MiB/s,w=20.8MiB/s][r=16.4k,w=5329 IOPS][eta 00m:00s]

test: (groupid=0, jobs=1): err= 0: pid=205075: Mon Feb 15 04:06:35 2021

read: IOPS=15.7k, BW=61.5MiB/s (64.5MB/s)(3070MiB/49937msec)

bw ( KiB/s): min=53288, max=66784, per=99.94%, avg=62912.34, stdev=2254.36, samples=99

iops : min=13322, max=16696, avg=15728.08, stdev=563.59, samples=99

write: IOPS=5259, BW=20.5MiB/s (21.5MB/s)(1026MiB/49937msec); 0 zone resets

...

What you care about are the lines starting with read: and write: under the test: line.

- Your read should have IOPS of at least 15k and bandwidth (BW) of at least 60 MiB/s.

- Your write should have IOPS of at least 5000 and bandwidth of at least 20 MiB/s.

Those are the specs from the Samsung T5 that we use, which work very well. We have also tested a slower SSD with read IOPS of 5k and write IOPS of 1k, and it has a very hard time keeping up with the ETH2 chain. If you use an SSD slower than the specs above, just be prepared that you might see a lot of missed attestations. If yours meets or exceeds them, then you're all set and can move on.

NOTE

If your SSD doesn't meet the above specs but it should, you might be able to fix it with a firmware update. For example, this has been experienced by the Rocket Pool community with the Samsung T7. Two of them fresh out of the box only showed 3.5K read IOPS and 1.2K write IOPS. After applying all available firmware updates, the performance was back up to the numbers shown in the above example. Check with your manufacturer's support website for the latest firmware and make sure your drive is up to date - you may have to update the firmware multiple times until there are no more updates left.

Last but not least, remove the test file you just made:

sudo rm /mnt/rpdata/test

# Setting up Swap Space

The Pi has 8 GB (or 4 GB if you went that route) of RAM. For our configuration, that will be plenty. Then again, it never hurts to add a little more. What we're going to do now is add what's called swap space. Essentially, it means we're going to use the SSD as "backup RAM" in case something goes horribly, horribly wrong and the Pi runs out of regular RAM. The SSD isn't nearly as fast as the regular RAM, so if it hits the swap space it will slow things down, but it won't completely crash and break everything. Think of this as extra insurance that you'll (most likely) never need.

# Creating a Swap File

The first step is to make a new file that will act as your swap space. Decide how much you want to use - a reasonable start would be 8 GB, so you have 8 GB of normal RAM and 8 GB of "backup RAM" for a total of 16 GB. To be super safe, you can make it 24 GB so your system has 8 GB of normal RAM and 24 GB of "backup RAM" for a total of 32 GB, but this is probably overkill. Luckily, since your SSD has 1 or 2 TB of space, allocating 8 to 24 GB for a swapfile is negligible.

For the sake of this walkthrough, let's pick a nice middleground - say, 16 GB of swap space for a total RAM of 24 GB. Just substitute whatever number you want in as we go.

Enter this, which will create a new file called /mnt/rpdata/swapfile and fill it with 16 GB of zeros.

To change the amount, just change the number in count=16 to whatever you want. Note that this is going to take a long time, but that's ok.

sudo dd if=/dev/zero of=/mnt/rpdata/swapfile bs=1G count=16 status=progress

Next, set the permissions so only the root user can read or write to it (for security):

sudo chmod 600 /mnt/rpdata/swapfile

Now, mark it as a swap file:

sudo mkswap /mnt/rpdata/swapfile

Next, enable it:

sudo swapon /mnt/rpdata/swapfile

Finally, add it to the mount table so it automatically loads when your Pi reboots:

sudo nano /etc/fstab

Add a new line at the end so that the file looks like this:

LABEL=writable / ext4 defaults 0 0

LABEL=system-boot /boot/firmware vfat defaults 0 1

UUID=1ade40fd-1ea4-4c6e-99ea-ebb804d86266 /mnt/rpdata ext4 defaults 0 0

/mnt/rpdata/swapfile none swap sw 0 0

Press Ctrl+O and Enter to save, then Ctrl+X and Enter to exit.

To verify that it's active, run these commands:

sudo apt install htop

htop

Your output should look like this at the top:

If the second number in the last row labeled Swp (the one after the /) is non-zero, then you're all set.

For example, if it shows 0K / 16.0G then your swap space was activated successfully.

If it shows 0K / 0K then it did not work and you'll have to confirm that you entered the previous steps properly.

Press q or F10 to quit out of htop and get back to the terminal.

# Configuring Swappiness and Cache Pressure

By default, Linux will eagerly use a lot of swap space to take some of the pressure off of the system's RAM. We don't want that. We want it to use all of the RAM up to the very last second before relying on SWAP. The next step is to change what's called the "swappiness" of the system, which is basically how eager it is to use the swap space. There is a lot of debate about what value to set this to, but we've found a value of 6 works well enough.

We also want to turn down the "cache pressure", which dictates how quickly the Pi will delete a cache of its filesystem. Since we're going to have a lot of spare RAM with our setup, we can make this "10" which will leave the cache in memory for a while, reducing disk I/O.

To set these, run these commands:

sudo sysctl vm.swappiness=6

sudo sysctl vm.vfs_cache_pressure=10

Now, put them into the sysctl.conf file so they are reapplied after a reboot:

sudo nano /etc/sysctl.conf

Add these two lines to the end:

vm.swappiness=6

vm.vfs_cache_pressure=10

Then save and exit like you've done before (Ctrl+O, Ctrl+X).

# Overclocking the Pi

By default, the 1.5 GHz processor that the Pi comes with is a pretty capable little device. For the most part, you should be able to validate with it just fine. However, we have noticed that on rare occasions, your validator client gets stuck working on some things and it just doesn't have enough horsepower to keep up with your validator's attestation duties. When that happens, you'll see something like this on the beaconcha.in explorer (opens new window) (described in more detail in the Monitoring your Node's Performance guide later on):

That inclusion distance of 8 means that it took a really long time to send that attestation, and you will be slightly penalized for being late. Ideally, all of them should be 0. Though rare, these do occur when running at stock settings.

There is a way to mitigate these, however: overclocking. Overclocking is by far the easiest way to get some extra performance out of your Pi's CPU and prevent those nasty high inclusion distances. Frankly, the default CPU clock of 1.5 GHz is really underpowered. You can speed it up quite a bit via overclocking, and depending on how far you take it, you can do it quite safely too.

Overclocking the Pi is very simple - it just involves changing some numbers in a text file. There are two numbers that matter: the first is the core clock, which directly determines how fast the ARM CPU runs. The second is overvoltage, which determines the voltage that gets fed into the ARM CPU. Higher speeds generally require higher voltage, but the Pi's CPU can handle quite a bit of extra voltage without any appreciable damage. It might wear out a little faster, but we're still talking on the order of years and the Pi 5 will be out by then, so no real harm done!

Rather, the real concern with overvoltage is that higher voltages lead to higher temperatures. This section will help you see how hot your Pi gets under a heavy load, so you don't push it too far.

WARNING

While overclocking at the levels we're going to do is pretty safe and reliable, you are at the mercy of what's called the "silicon lottery". Every CPU is slightly different in microscopic ways, and some of them can simply overclock better than others. If you overclock too far / too hard, then your system may become unstable. Unstable Pis suffer from all kinds of consequences, from constant restarts to completely freezing. In the worst case, you could corrupt your microSD card and have to reinstall everything from scratch!

By following the guidance here, you have to accept the fact that you're running that risk. If that's not worth it for you, then skip the rest of this section.

# Benchmarking the Stock Configuration

Before overclocking, your should profile what your Pi is capable of in its stock, off-the-shelf configuration. There are three key things to look at:

- Performance (how fast your Pi calculates things)

- Temperature under load (how hot it gets)

- Stability (how long it runs before crashing)

We're going to get stats on all three of them as we go.

# Performance

For measuring performance, you can use LINPACK. We'll build it from source.

cd ~

sudo apt install gcc

wget http://www.netlib.org/benchmark/linpackc.new -O linpack.c

...

cc -O3 -o linpack linpack.c -lm

...

sudo mv linpack /usr/local/bin

rm linpack.c

Now run it like this:

linpack

Enter array size (q to quit) [200]:

Just press enter to leave it at the default of 200, and let it run.

When it's done, the output will look like this:

Memory required: 315K.

LINPACK benchmark, Double precision.

Machine precision: 15 digits.

Array size 200 X 200.

Average rolled and unrolled performance:

Reps Time(s) DGEFA DGESL OVERHEAD KFLOPS

----------------------------------------------------

512 0.70 85.64% 3.76% 10.60% 1120802.516

1024 1.40 85.70% 3.74% 10.56% 1120134.749

2048 2.81 85.71% 3.73% 10.56% 1120441.752

4096 5.62 85.69% 3.74% 10.57% 1120114.452

8192 11.23 85.67% 3.74% 10.59% 1120277.186

What you need to look at is the last row, in the KFLOPS column.

This number (1120277.186 in the above example) represents your computing performance.

It doesn't mean anything by itself, but it gives us a good baseline to compare the overclocked performance to.

Let's call this the stock KFLOPS.

# Temperature

Next, let's stress the Pi out and watch its temperature under heavy load.

First, install this package, which will provide a tool called vcgencmd that can print details about the Pi:

sudo apt install libraspberrypi-bin

Once this is installed, reboot the Pi (this is necessary for some new permission to get applied). Next, install a program called stressberry. This will be our benchmarking tool. Install it like this:

sudo apt install stress python3-pip

pip3 install stressberry

source ~/.profile

NOTE

If stressberry throws an error about not being able to read temperature information or not being able to open the vchiq instance, you can fix it with the following command:

sudo usermod -aG video $USER

Then log out and back in, restart your SSH session, or restart the machine and try again.

Next, run it like this:

stressberry-run -n "Stock" -d 300 -i 60 -c 4 stock.out

This will run a new stress test named "Stock" for 300 seconds (5 minutes) with 60 seconds of cooldown before and after the test, on all 4 cores of the Pi.

You can play with these timings if you want it to run longer or have more of a cooldown, but this works as a quick-and-dirty stress test for me.

The results will get saved to a file named stock.out.

During the main phase of the test, the output will look like this:

Current temperature: 41.3°C - Frequency: 1500MHz

Current temperature: 41.3°C - Frequency: 1500MHz

Current temperature: 41.8°C - Frequency: 1500MHz

Current temperature: 40.9°C - Frequency: 1500MHz

Current temperature: 41.8°C - Frequency: 1500MHz

This basically tells you how hot the Pi will get. At 85°C, the Pi will actually start to throttle itself and bring the clock speed down so it doesn't overheat. Luckily, because you added a heatsink and a fan, you shouldn't get anywhere close to this! That being said, we generally try to keep the temperatures below 65°C for the sake of the system's overall health.

If you want to monitor the system temperature during normal validating operations, you can do this with vcgencmd:

vcgencmd measure_temp

temp=34.0'C

# Stability

Testing the stability of an overclock involves answering these three questions:

- Does the Pi turn on and get to a login promp / start the SSH server?

- Does it randomly freeze or restart during normal operations?

- Does it randomly freeze or restart during heavy load?

For an overclock to be truly stable, the answers must be yes, no, and no.

There are a few ways to test this, but the easiest at this point is to just run stressberry for a really long time.

How long is entirely up to you - the longer it goes, the more sure you can be that the system is stable.

Some people just run the 5 minute test above and call that good if it survives; others run it for a half hour; others run it for 8 hours or even more.

How long to run it is a personal decision you'll have to make based on your own risk tolerance.

To change the runtime, just modify the -d parameter with the number of seconds you want the test to run.

For example, if you decided a half-hour is the way to go, you could do -d 1800.

# Your First Overclock - 1800 MHz (Light)

The first overclock we're going to do is relatively "light" and reliable, but still provides a nice boost in compute power. We're going to go from the stock 1500 MHz up to 1800 MHz - a 20% speedup!

Open this file:

sudo nano /boot/firmware/usercfg.txt

Add these two lines to the end:

arm_freq=1800

over_voltage=3

Then save the file and reboot.

These settings will increase the CPU clock by 20%, and it will also raise the CPU voltage from 0.88v to 0.93v (each over_voltage setting increases it by 0.025v).

This setting should be attainable by any Pi 4B, so your system should restart and provide a login prompt or SSH access in just a few moments.

If it doesn't, and your Pi stops responding or enters a boot loop, you'll have to reset it - read the next section for that.

# Resetting After an Unstable Overclock

If your Pi stops responding, or keeps restarting over and over, then you need to lower the overclock. To do that, follow these steps:

- Turn the Pi off.

- Pull the microSD card out.

- Plug the card into another Linux computer with a microSD adapter.

NOTE: This has to be another Linux computer. It won't work if you plug it into a Windows machine, because Windows can't read the

ext4filesystem the SD card uses!* - Mount the card on the other computer.

- Open

<SD mount point>/boot/firmware/usercfg.txt. - Lower the

arm_freqvalue, or increase theover_voltagevalue. NOTE: do not go any higher than over_voltage=6. Higher values aren't supported by the Pi's warranty, and they run the risk of degrading the CPU faster than you might be comfortable with. - Unmount the SD card and remove it.

- Plug the card back into the Pi and turn it on.

If the Pi works, then great! Continue below.

If not, repeat the whole process with even more conservative settings.

In the worst case you can just remove the arm_freq and over_voltage lines entirely to return it to stock settings.

# Testing 1800 MHz

Once you're logged in, run linpack again to test the new performance.

Here's an example from our test Pi:

linpack

Enter array size (q to quit) [200]:

...

Reps Time(s) DGEFA DGESL OVERHEAD KFLOPS

----------------------------------------------------

512 0.59 85.72% 3.75% 10.53% 1338253.832

1024 1.18 85.72% 3.75% 10.53% 1337667.003

2048 2.35 85.72% 3.75% 10.53% 1337682.272

4096 4.70 85.73% 3.75% 10.53% 1337902.437

8192 9.40 85.71% 3.76% 10.53% 1337302.722

16384 18.80 85.72% 3.75% 10.52% 1337238.504

Again, grab the KFLOPS column in the last row.

To compare it to the stock configuration, simply divide the two numbers:

1337238.504 / 1120277.186 = 1.193668

Alright! That's a 19.4% boost in performance, which is to be expected since we're running 20% faster. Now let's check the temperatures with the new clock speed and voltage settings:

stressberry-run -n "1800_ov3" -d 300 -i 60 -c 4 1800_ov3.out

You should see output like this:

Current temperature: 47.2°C - Frequency: 1800MHz

Current temperature: 48.7°C - Frequency: 1800MHz

Current temperature: 47.7°C - Frequency: 1800MHz

Current temperature: 47.7°C - Frequency: 1800MHz

Current temperature: 47.7°C - Frequency: 1800MHz

Not bad, about 6° hotter than the stock settings but still well below the threshold where we'd personally stop.

You can run a longer stability test here if you're comfortable, or you can press on to take things even higher.

# Going to 2000 MHz (Medium)

The next milestone will be 2000 MHz. This represents a 33.3% boost in clock speed, which is pretty significant. Most people consider this to be a great balance between performance and stability, so they stop the process here.

Our recommendation for this level is to start with these settings:

arm_freq=2000

over_voltage=5

This will boost the core voltage to 1.005v.

Try this out with the linpack and stressberry tests.

If it survives them, then you're all set. If it freezes or randomly restarts, then you should increase the voltage:

arm_freq=2000

over_voltage=6

That puts the core voltage at 1.03v, which is as high as you can go before voiding the warranty. That usually works for most Pis. If it doesn't, instead of increasing the voltage further, you should lower your clock speed and try again.

For reference, here are the numbers from our 2000 run:

linpack

Enter array size (q to quit) [200]:

...

Reps Time(s) DGEFA DGESL OVERHEAD KFLOPS

----------------------------------------------------

512 0.53 85.76% 3.73% 10.51% 1482043.543

1024 1.06 85.74% 3.73% 10.53% 1481743.724

2048 2.12 85.74% 3.72% 10.54% 1482835.055

4096 4.24 85.73% 3.74% 10.53% 1482189.202

8192 8.48 85.74% 3.73% 10.53% 1482560.117

16384 16.96 85.74% 3.73% 10.53% 1482441.146

That's a 32.3% speedup which is in-line with what we'd expect. Not bad!

Here are our temperatures:

Current temperature: 54.0°C - Frequency: 2000MHz

Current temperature: 54.5°C - Frequency: 2000MHz

Current temperature: 54.0°C - Frequency: 2000MHz

Current temperature: 54.5°C - Frequency: 2000MHz

Current temperature: 55.5°C - Frequency: 2000MHz

An increase of 7 more degrees, but still under our threshold of 65°C.

# Going to 2100 MHz (Heavy)

The highest we're going to take the Pi in this guide is 2100 MHz. This represents a solid 40% speedup over the stock configuration.

NOTE: Not all Pi's are capable of doing this while staying at over_voltage=6.

Try it, and if it breaks, go back to 2000 MHz.

This is the configuration we use on our Pi:

arm_freq=2100

over_voltage=6

For reference, here are our results:

linpack

Enter array size (q to quit) [200]:

...

Reps Time(s) DGEFA DGESL OVERHEAD KFLOPS

----------------------------------------------------

512 0.50 85.68% 3.76% 10.56% 1560952.508

1024 1.01 85.68% 3.76% 10.56% 1554858.509

2048 2.01 85.70% 3.74% 10.56% 1561524.482

4096 4.03 85.72% 3.73% 10.55% 1560152.447

8192 8.06 85.72% 3.73% 10.54% 1561078.999

16384 16.11 85.73% 3.73% 10.54% 1561448.736

That's a 39.4% speedup!

Here are our temperatures:

Current temperature: 59.4°C - Frequency: 2100MHz

Current temperature: 58.9°C - Frequency: 2100MHz

Current temperature: 58.4°C - Frequency: 2100MHz

Current temperature: 59.4°C - Frequency: 2100MHz

Current temperature: 58.9°C - Frequency: 2100MHz

Just shy of 60°C, so there's plenty of room. We are happy with this performance and temperature range, so this is what we run.

# Next Steps

And with that, your Pi is up and running and ready to run Rocket Pool! Move on to the Choosing your ETH Clients section.